How the Conasauga Shaped Whitfield County

/In my last article, I discussed the history of Kudzu, a plant that we introduced into our environment. Today, I want to focus an aspect of our environment that has been here long before we were introduced, the Conasauga River. The Conasauga River begins in Polk County, Tennessee and winds through Whitfield and Murray Counties before connecting with the Oostanaula River and pouring into the Gulf of Mexico. It is one of the most biodiverse rivers in North America and has played a part in the history of this area through all generations.

The Conasauga gets its name from the Cherokee word for “grass.” The river was important to the Cherokee’s way of life and their actions had an impact on the river as well. James Vann, a key figure among the Cherokee for his wealth and business, invited Moravian missionaries so the children could be educated by them. It is through an entry from one of these missionaries, Anna Rosina, that we know Cherokee would travel to this area for the hunting season and counted on it for meat.

We also know they grew numerous crops and counted on the land for food themselves and materials to trade. The farming practices of the Cherokee and later the settlers and industries has long been impacting the soil. Cotton in particular can be harsh on the soil and the farming can erode or exhaust the soil surrounding the river.

The Conasauga made a name for itself among settlers as a way of easy transport. The portage was a good alternative to the Mississippi River. In 1827, there was even a report of 12,000 gallons of whiskey being moved through this route.

This was also when the resources including the Conasauga River currently used by the Cherokee began to capture the attention of the government. In 1828 the United States government began surveying 160 parcels of land that would be doled out. Two years later, The Cherokee Removal Act led to the tragic Trail of Tears as the Cherokee lost their land and were forced to leave the area.

The Georgia land lottery where those parcels were given out accelerated the rate of logging and privatization of the region surrounding the Conasauga River. While the Cherokee attempted to legally fight their removal and selling of their land, none of their attempts had success.

Business grew after the Georgia land lottery. There were many mills and logging operations founded and large farms were established. This era of people still counted on the Conasauga river for their daily work, transportation, and bounty. Levi Branham, a slave in Murray County during the 1850’s and 1860’s, mentions in his book, My Life and Travels, finding a fishing basket in the river filled with “five or six trout weighing from four or five pounds.” These personal accounts give us a hint of the plentiful wildlife during this period.

The logging industry around the Conasauga reached its height in the 1920’s. Transportation advancements would cause some struggles through the Conasauga. Steam and river boats would be able to come down the river when high tide raised the water level, but it would not be long before the river would become too shallow and too narrow. Instead, the railways built decades earlier were more relied on.

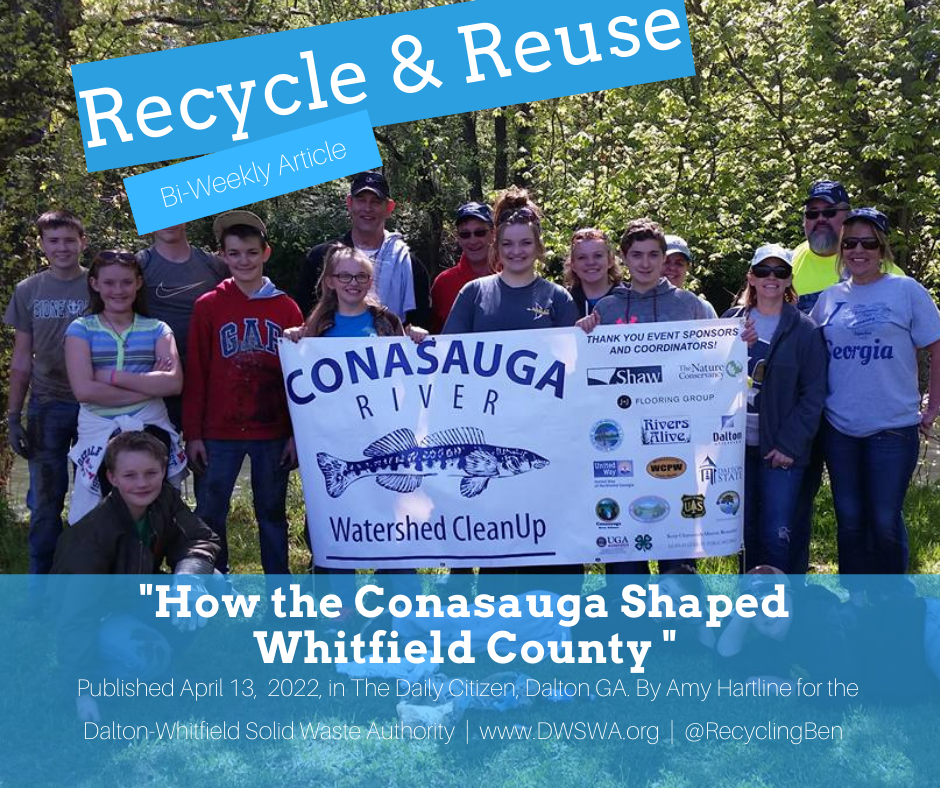

Today, the Conasauga is used by the carpet industry in Whitfield County. It is also used for recreation such as kayaking and canoeing through the peaceful waters. It is home to around a dozen endangered fish including the Conasauga Logperch, a fish only found in the Conasauga.

For centuries people have enjoyed the use of the river for industry and for emotional peace. It has been critical to the history and growth of this region, but that journey can also leave it vulnerable. Farming can impact the soil, industry can reduce the resources of the environment surrounding the river, and the general public needs the water for everyday life. When possible, help keep this river and its wildlife thriving by reducing your water usage, disposing of household hazardous waste correctly, and cleaning up the watershed that drains into the river.